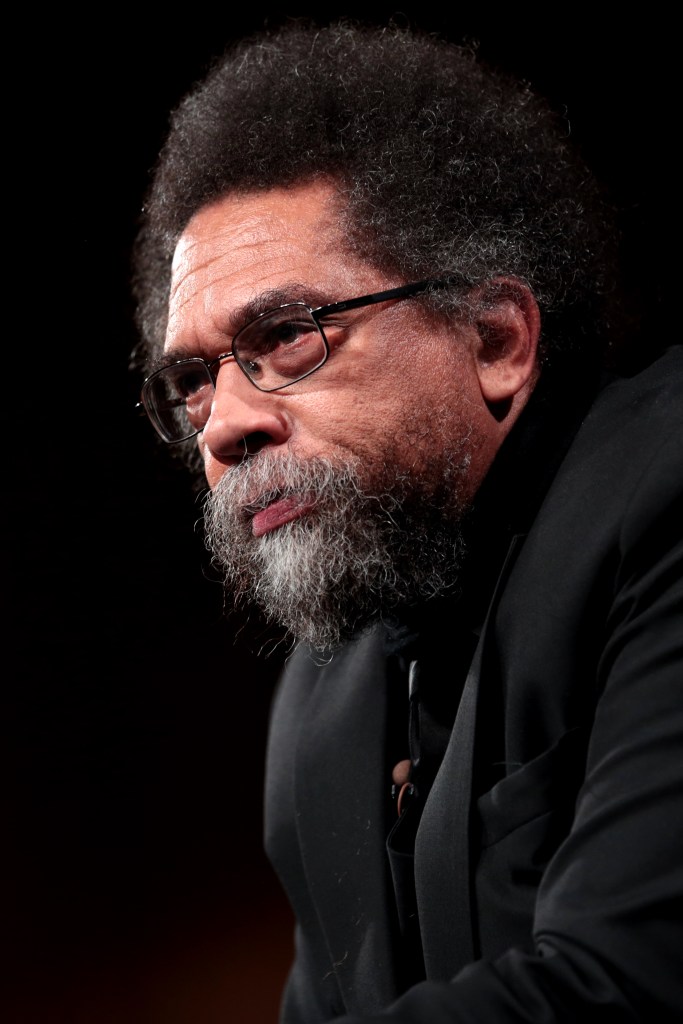

About this time last year, The New Republic nominated Cornel West as their “Charlatan of the Year” for running as an independent in 2024’s presidential election. Now that that contest is up, it’s safe to say that West was a political non-factor among non-factors. His votes melted almost immediately into the nameless mass of 388,817 “Other Candidate” ballots, which is roughly half the total that Chase Oliver (?) took home.

The article was written by David Masciotra, whose incisive Exurbia Now I reviewed earlier this year. Masciotra is a thoughtful chronicler of the American Left and its metamorphoses over the last four decades, and his catalog spans an impressive range over American culture generally. He’s also faced dressing-downs in the past for his criticisms of West – since West, like many public intellectuals who’ve mastered the lecture and cable circuit, has no shortage of loyalists – and I have no business piling on. Masciotra’s critique, for the most part, is sound. I can speak comfortably from this position of hindsight, knowing now that West’s candidacy was never a threat to anybody, and say that perhaps Masciotra leaned a bit too hard on the man.

Easy for me to say.

I was only reminded of TNR’s article because I’ve been working my way through recordings of West’s 2024 Gifford Lectures this last week. This post isn’t meant to cover the logic (or illogic) of third-partyism – I want to write instead about West’s artistic side – but I will say a few things in brief. Yes, in the end, West was a non-player in the election, but even if he could have made a difference:

- In December 2023, when the article was published, President Biden was the unquestioned Democratic nominee and was still a full seven months away from withdrawing from the race – a call that was almost unanimously affirmed even by his own diehard supporters.

- When the article was published, West was perhaps the only charismatic candidate on the Left launching any kind of “internal opposition” to Biden’s run. (Who else was there – Dean Phillips?)

- The threat of a serious electoral challenge from West may (in some alternate reality) have been one (small) part of a movement to reconsider Biden’s candidacy an entire year before that conversation actually took place, following “the debate heard round the world.”

- Many Democratic strategists – the same who opposed West’s candidacy as the vanity run it may have been – now lament the lack of a “real” primary, and the lack of time for Harris’s campaign to get off the ground, blaming those factors for Harris’s defeat. A third-party challenge from the Left was, perhaps, one way to deal with these factors far enough in advance to make some kind of a difference.

- Even if it never led to a shake-up at the top of the ticket, the purpose of a “spoiler candidacy” like West’s is not to win but to exert real pressure on the closest ally with the best chance of winning – and to get some kind of humane concessions from them before they dish up their usual tasteless election-year-milquetoast gloop.

Enough about the presidential run, which is the least interesting thing about West’s career even in the last few years.

Watching the Gifford Lectures this month (and several of West’s guest lectures from elsewhere) brought me my first sustained dose of West’s rhetoric. This was the first I’d experienced of West’s infamous web-spinning: his deep familiarity with, and playful references to, the canons of world thought – of philosophy, poetry, novels, plays, theology, and, importantly, music.

Now, a quick note to set up my next point: unlike many wonderful writers and scholars I know, I never had to be converted to the liberal arts. I’ve always bought into the corny platitudes that college recruiters shell out about becoming a “versatile thinker.” For as long as I can remember, I always believed that something tethered all the arts together; that there was some mystical union – some Platonic canon – that gathered together all forms of human expression over the ages, and that they really did and really could be held in conversation with one another – and that they all really mattered in the grand scheme of things. I’m not exaggerating when I say that this was, and still is, a nearly religious ideal for me. I won’t go into that here – only to say that this faith has been scattered over some very rocky soil in the last decade or so, both in and out of academies.

West, of course, is from an older generation of scholars, and his lower-case-l-liberal use of the canon was probably not so unusual in the past. (I’m thinking especially of the High Romantic Harold Bloom, who sang a 40-year swan song over the waning of just this kind of hallowed treatment of literature before his death in 2019) West knows the literary greats intimately. But to hear West speak about other arts, and especially about music and musicians – jazz, the blues, John Coltrane, Curtis Mayfield, Nina Simone – is astonishing. It’s far different from the way that any other contemporary critics – at least the ones I’ve read recently – approach the arts.

To take a basically random example, consider the cultural criticism of Mark Greif, the n+1 founder whose 2016 collection Against Everything covered Keeping Up with The Kardashians, Nas, “Octomom,” the lyrics of Radiohead, and other so-called “pop culture phenomena.” Here, as in almost every other example of “Media Studies” that I can think of, there’s an overdetermined, almost deadly seriousness to the treatment of the subject matter. The absolute refusal of “Media Studies” to make aesthetic divisions between what their audience instinctively recognizes as “high” and “low culture” sometimes feels like a challenge to the reader: What, aren’t you going to say anything about my Kardashians chapter? Not quite what you expected? Was that a smirk I saw there? I don’t think Greif necessarily wants this reaction – but at no point does the reader get the sense that these songs/TV shows/films/individuals are anything more than proxies for the writer’s own analytical flourishes. The attention is entirely on the writer’s brilliance: look at all the insights I can glean from the cultural detritus you, the common middlebrow reader, probably don’t even think twice about.1

Not so when West caps off his tangents with a lyric from Curtis Mayfield. In short, West thinks these artists have something to say – their works are in conversation with Nietzsche and Chekhov and Lukács and Heidegger and all the rest, and not just in the pandering way that our disciplines use that term. They aren’t merely “cultural artifacts” or objects of “ethnographic study.” And therein, I think, lies one of the most vital effects of West’s public lectures: it actually allows the arts a place in the most meaningful conversations of history.

And one last note: West’s reading of Christianity – his unbelievably consistent insistence on the equal dignity and worth of every human life; his welcoming of even ruthless opponents as “dear brothers/sisters” – is a welcome thaw for the chilling hoarfrost of radical politics. It’s given him a universal conception of justice and solidarity that makes the factory-grade Marxism of his compatriots look provincial and clannish by comparison. His so-called “revolutionary Christianity” exalts the poor and the low-caste while leaving a space, even theoretically, for the publicans – the Lazaruses as well as the imperial collaborators like Zacchaeus.

- (Not a dig at Greif specifically — this is a generalized “I” shared by, let’s say, the broader discipline of “cultural studies”) ↩︎