There is too much to say about the Year of Our Lord 2024 – too many moments of joy and tragedy, personally and geopolitically – so I’ll limit myself to writing about books and some other media.

If you counted up the number of words that passed in front of my eyeballs in 2024, I think I read more this year than in any other. I fell well short of my goal for books but made up the difference in student essays and other “required reading” – or that’s what I’m letting myself believe.

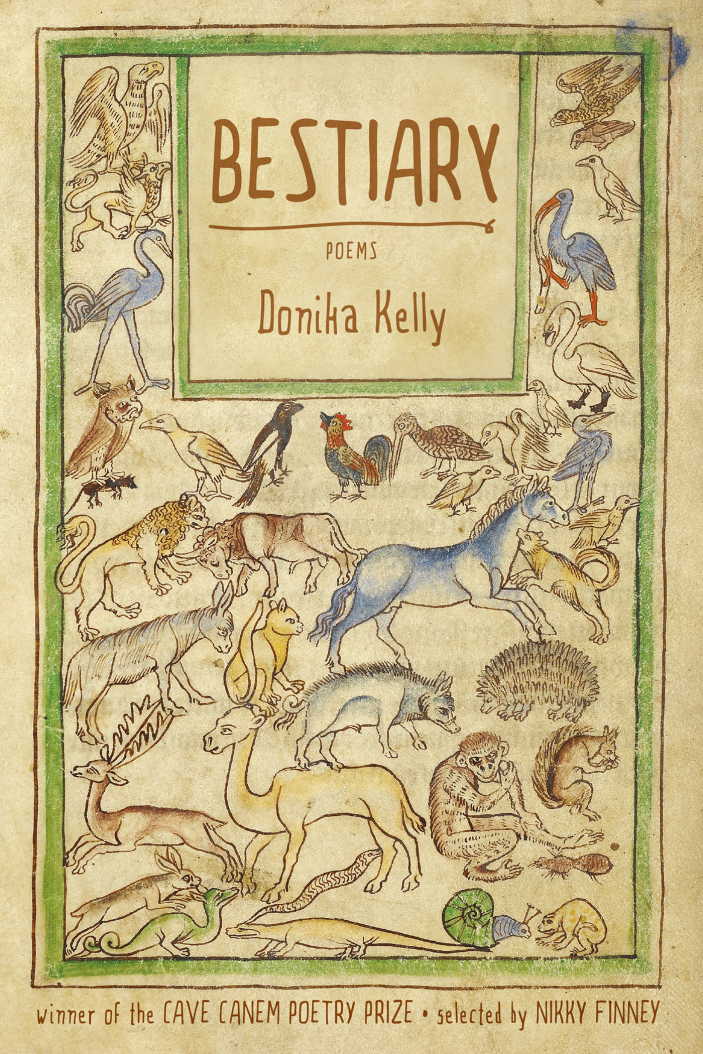

The books I’d solemnly vowed to finish by the end of this year were crowded out by a mounting stack of overdue library books and others that demanded immediate attention. And there was a theme to this year’s reading that I wouldn’t have predicted this time last year. My end-of-year tally was unexpectedly heavy on new indie releases (for review purposes) and religion books (for personal reasons) and unforgivably light on poetry and fiction. In 2025 I hope (as always) to be more disciplined.

I have pet projects for the new year and some more serious ones. I’m still working through a stack of books I should have finished long ago (I know, “should” is relative, but many of these were assigned readings, so “should” is appropriate). Augustine and Kierkegaard are at the top. John Donne is up there too. The list is embarrassingly long.

In 2025 I want to finish all the parts of the Bible I haven’t yet read (and reread as much as I can of what I already have). It becomes more difficult to do the more seriously I take it. After that, I want to finish the Mishnah, the Quran, and the Book of Mormon, in that order – I’ll save my explanations for another time.

Looking back over the list of everything I read this year, I’m struck by how underwhelming so much of it seems. True sparks were fewer and farther between than in almost any year I have on record. That’s not to say I read no masterpieces – but somehow, on the whole, I don’t think I had nearly as much fun with these titles as I usually do. Perhaps I let circumstance and gut-instinct guide my reading choices too often, and I postponed too many books that would have genuinely captured my interest.

But I am unspeakably grateful to be alive and reading. There is much, much, much more to explore.

Some highlights:

Books

Highly, Highly Recommended:

- The Plot Against America – Philip Roth (and the excellent HBO miniseries adaptation from 2020)

- A Sand County Almanac – Aldo Leopold

- Tom Lake: A Novel – Ann Patchett

- The Dearly Beloved: A Novel – Cara Wall

- Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics – Ross Douthat

- The Marriage Portrait: A Novel – Maggie O’Farrell

- Summa Contra Gentiles, Book One: God – St. Thomas Aquinas (a surprisingly readable ease-in to scholastic theology)

Most Beautiful Prose: The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver

- Every now and then a book comes along that makes my writerly self despair of ever coming close to its triumphs. Kingsolver’s multi-decade narrative of an American missionary family in the Belgian Congo had that (not unpleasant) effect on me. Kingsolver masterfully juggles the voicings and psychological profiles of five very different narrators while telling an ambitious and genuinely gripping story of despair and change. This is not a perfect novel, but it is probably the closest thing I’ve read in a very long time.

Most Fun: Dracula by Bram Stoker

- Everything has already been said about Dracula, so here are two quick thoughts. One: Dracula is somehow even more fun to read when you already know the major narrative beats; that’s the sign of a superbly-crafted, dread-inducing “slow burn.” Two: the comradeship formed between the book’s heroes in the second and third acts seems like a window onto another world. Maybe that’s my post-COVID, Millennial/Gen-Z isolation talking – but it’s almost inconceivable to imagine this sort of brotherly attachment to a shared higher calling cropping up very often among adults today. That level of bond may be limited to the military or the consecrated religious life. Perhaps the Victorians were more sentimental, or perhaps I need to get out more. At any rate: I’ll probably return to Dracula every October from here on out.

Most Aggravating: Origin by Dan Brown

- It’s a little silly to complain about a thriller that was published back in 2017. But the latest Robert Langdon mystery is a rare canker of a book that does something worse than bore its readers: it calls them stupid. Origin takes on religion as its subject – a scandal (as though The Da Vinci Code, Angels and Demons, and Inferno hadn’t done the same thing) – and never ceases to be impressed with itself for this decision. Brown treats atheism as a chic vanguard force in a European context that is and has been, by actual reckoning and reputation, thoroughly secularized. And the book’s central figure, Edmond Kirsch, is a creation that would have felt dated even two decades ago in the New Atheist publishing blitz. Brown’s characters are scandalized and spellbound in ways that would tickle their real-world counterparts. Worst of all: Origin spends most of its pages teasing an earth-shattering revelation – a revelation so profound that it launches the “world’s most brilliant religionists” into an existential headspin – and then actually delivers it. The revelation is piddling (a rehash of uncontroversial ideas about abiogenesis and a future “singularity”), but we get the sense that we’re meant to be as impressed as are the smartest people in Brown’s fictional world. And then our hero Robert Langdon, speaking as Brown’s stand-in, ends with a note of magnanimous “tolerance” for those (read: you and me) who may not be ready to face this brave new truth. I hate when books do this. And this isn’t even the worst offender I read this year. Origin makes me think that Dan Brown, for all his globetrotting, lives in an odd simulacrum of the modern world.

Other media:

Highly Recommended 2024 Films:

- Anora

- Give it 40 minutes and you’ll find that this is not at all the movie you first walked into. This is a hilarious, heartbreaking, very Russian sort of black comedy.

- Back to Black

- Musician biopics from Hollywood usually feel a little overcooked, but this one is grounded by serious musical talent and retains a certain authentic messiness.

- Between the Temples

- On a budget of exactly $75, this team did something remarkably weird and (I’m going to use the term for the second time) heartbreaking.

- Conclave

- A little corny, and more than a little preachy (which makes sense) – but full of wonderful performances.

- Dune: Part Two

- There is no such thing as a perfect Dune adaptation. This, however, is a solid one.

- Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

- This was a hard sell (that nobody asked for), which made its triumphs all the more wonderful.

- Longlegs

- Ignore the haters. It did overpromise in its ad blitz; it does fall flat in the third act when its mysteries are finally answered. But the first two thirds of this film are masterful horror storytelling.

- We Live in Time

- Once again, I need my favorite word: “heartbreaking.” A quiet, humbling take on parenthood, commitment, and growing up.

Highly Recommended TV series (ones I first came across in 2024):

- The Bear (Max)

- The show’s third season may have been its weakest, but this is still far-and-away the best drama in the game. Almost unbelievably good.

- Civilisation: A Personal View by Kenneth Clarke (BBC)

- Demands multiple viewings – this was my third time straight through from start to finish (while waiting for PBS to make a second season of their successor series Civilizations)

- Rick Steves’ Art of Europe (PBS)

- A sunnier take on the same ground covered by Kenneth Clarke.

- Country Music: A Film by Ken Burns (PBS)

- I only just started this one, but it still has to go on the list.

- Only Murders in the Building (Hulu)

- I’m only two episodes into this one, but it already has to go on the list.

Best overall series: The Young Pope and The New Pope (HBO)

- Paolo Sorrentino’s baroque 2016 and 2020 miniseries may be the most important treatment of religious faith in popular culture of the 21st century. Overstatement or not, The Young Pope and The New Pope form a layered and beautiful narrative. Visual decadence and obvious clichés about piety abound, not always in productive ways, and Sorrentino is clearly in love with his own set pieces. Some of the subplots are more affecting than others. And as with this year’s Conclave, there’s an ultimately predictable (and dramatically uncompelling) softness that seeps in around the rougher edges at the narrative’s close. But even so: Popes Pius XIII (Jude Law) and John Paul III (John Malkovich) are some of the most interesting protagonists to appear on HBO or anywhere else. The story itself, thanks to the scale of the burdens shouldered by our characters, is as intense as anything in Game of Thrones or House of Cards. There are moments of this story that I believe will profoundly move any viewer patient enough to give it a try. The series have my imprimatur.

Highly Recommended Albums (that I first heard this year):

- Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, Damn the Torpedoes (1979)

- Fleetwood Mac, Tusk (1979)

- Lou Reed, New York (1989)

- Lucinda Williams, Car Wheels On a Gravel Road (1998)

- American Football, American Football (1999)

- Ryan Adams, Gold (2001)

- Mk.gee, Two Stars & The Dream Police (2024)

- MJ Lenderman, Manning Fireworks (2024)

Recommended musical artists in general (that I first heard this year):

- Charley Crockett

- Maggie Rogers

- English Teacher

- Dinosaur Jr.

- Son Volt

- The Carter Family

- John Fahey

- The Louvin Brothers

- Lonnie Holley

- Soul Coughing

- Superchunk

- Traveling Wilburys

- Mk.gee

- MJ Lenderman

Highly recommended podcasts (that I listened to most frequently this year):

- In Our Time (BBC)

- Dollar Country (WTFC Radio Lawrence Kansas) – thanks to Justin Randel for recommending

- [Abridged] Presidential Histories with Kenny Ryan

- Premier Unbelievable: Ask N. T. Wright Anything

- The Jewish History Podcast with Rabbi Yaakov Wolbe

- Lectures in History (CSPAN)

- Humane Arts (Wesley Cecil)

- Westminster Presbyterian Church at Rock Tavern, New York (sermons)